SILICON VALLEY / TAIWAN

Manufacturing

The Semiconductor Is an Accretion of Place

BY ANN CHEN & INGRID BURRINGTON

Baoshan Reservoir, Taiwan. PHOTO BY ANN CHEN.The complexity of semiconductors partly comes from the fact that making a stone store and circulate electrons is some weird deep magic. Materials have to be precisely calibrated and prepared for manufacture in the void of laboratory conditions. The process of making computer chips is extraordinarily complicated, but what they actually do is pretty simple. Semiconductors are exactly that: semi-conductive, which is to say selectively conductive, capable of storing and transmitting electrical energy. At its most simplified state, digital computation is the storage and circulation of electrons within and via chemically transformed metals.

The conditions of chip manufacture require extraordinarily controlled environments in part because the actual object of control is so infinitesimally small that any foreign matter may alter its conditions. The cleanliness of the computer chip “clean room” is a caustic cleanliness, burning away that which doesn’t belong: dust, hair, any traces of organic life.

The irony of this intense purification process and incendiary cleanliness is that the semiconductor is also the sum of a fundamentally global process: they bear no traces of the hundreds of thousands of hands, gallons of water, or gigawatts of energy that go into their production.

Here is a story of one of those landscapes that chip manufacture so insistently tries to burn away:

A lot of writing about computation and semiconductors deems both as crucial to building the future. For Taiwan, semiconductors are framed as necessary for there to even be an independent Taiwanese future. But to build that future, the state borrows against it by depleting resources and prioritizing industry growth above all else. While the conditions of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry are in many ways unique and geographically specific, they’re also shaped by those narratives around semiconductors and someone’s idea of a necessary future–a narrative that was honed in the very early years of the industry in Silicon Valley, a place where the environmental history of chip manufacture is also fraught.

The labor and community organizing that took place in Silicon Valley in the 1970s and 1980s did bring about some crucial, concrete changes in environmental and worker health protections. Specific dangerous chemicals were investigated and eventually phased out of the manufacturing process, and

the standards for safety in manufacturing facilities was raised. But the effects linger. Chip manufacture was outsourced to elsewhere in the world, events like what happened in California would repeat in new landscapes. Perhaps one silver lining to this repetition is that across these new landscapes and Silicon

Valley, new solidarities and networks emerged.

SILICON VALLEY

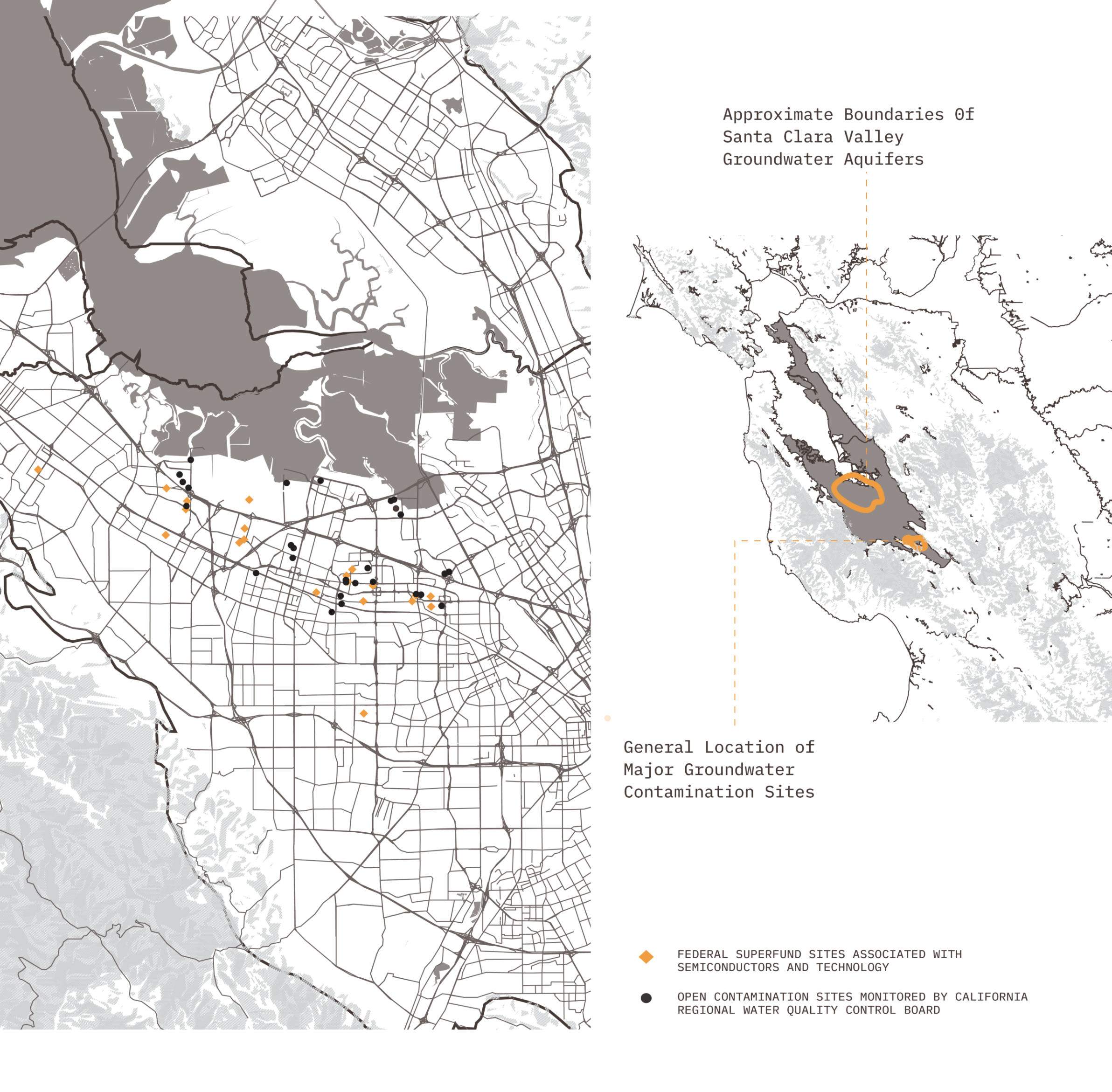

Before the Santa Clara Valley was known for software, it was known for hardware–the silicon chips at the heart of digital computing, without which there would be no software industry to begin with. But before hardware, the valley was known for agriculture. The moderate climate and rich groundwater aquifers made it a good place for fruit orchards, which became a key source of working-class jobs in the region along with canneries. Stanford University tends to get a lot of credit for helping establish an electronics industry in the Santa Clara Valley through creating the Stanford Industrial Park, a novel publicprivate partnership between Stanford and the city of Palo Alto to build manufacturing facilities on university land and recruit companies to set up shop there.

This suburban appearance contributed to the public misunderstanding that chip manufacture was environmentally neutral, absent of the smokestacks and visible pollution typically associated with “dirty” industries. The language of chip manufacture, with its emphasis on “clean rooms” and purification processes, also shaped public perceptions.

The harms of chemicals used in chip manufacture may not have been well-understood by residents, but they were increasingly understood by the largely immigrant and female workforce in Silicon Valley’s chip fabs. In the years prior to the discovery of the groundwater contamination, workers had little recourse when trying to find out more about the health impacts of the chemicals used at their jobs, and companies had little interest in studying those impacts.

Like semiconductor manufacturing, forensic science demands extreme precision and lived experience is wildly imprecise full of variables beyond the scope of workplace chemicals that could undermine what, to a worker, would seem to be an obvious causal connection Silicon Valley residents faced similar challenges in the aftermath of the groundwater contamination scandal.

Superfund and Open Contamination Sites in the Santa Clara Valley

From left to right: California monitoring well, Santa Clara Valley. PHOTO BY INGRID BURRINGTON. Keya Creek Waste Outlet, Taiwan. PHOTO BY ANN CHEN. Kaohsiung River, Taiwan. PHOTO BY ANN CHEN.TAIWAN

The Taiwanese government began seriously investing in technology and hardware manufacture in the 1970s, a few years after its expulsion from the United Nations following Western countries normalizing relations with The People’s Republic of China. “Industrial upgrading” was seen as a key strategy for

legitimizing the now-unrecognized state: economic recognition in the absence of diplomatic recognition. (It also was perceived as a “cleaner” alternative to more visibly polluting industries that had grown in prominence on the island and become a source of controversy and civil unrest.) Around this time, state technocrats traveled to the United States to tour some of Silicon Valley’s famous industrial and research parks, drawing on the region’s model with the creation of statebacked Science Parks. The first of these parks opened in 1980 in Hsinchu.

Like Silicon Valley, high tech industrial development replaced the agricultural land that recently preceded it. Generally, histories of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry jump from the Hsinchu Science Park’s creation in 1980 to the founding of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacture Company (TSMC) in 1987, the company that would completely transform the manufacturing model for computer chips and declare the rest history. In this narrative, the expansion of the Science Park model to other parts of the island and TSMC’s growth are both framed as bulwarks against Chinese imperialist aggression. This framing tends to make TSMC and the science parks seem both inevitable and entirely uncontested. What gets left out are the land grabs, pollution, and the grassroots community organizing in response to both that happened in concert with Taiwan’s technological development.

While grassroots organizations lobbied for and successfully achieved some increased oversight and regulation of the science parks, the increasing political tensions between Taiwan and China, spurred on by US involvement, has made any criticism of the semiconductor industry and industry giants like TSMC difficult.

Today, TSMC is frequently referred to in Taiwan as 護國神社 (hù guó qún shan), “the mountain range protecting the country”, perceivably the “silicon shield”, preventing Chinese aggression and maintaining US interests in protecting Taiwan.

Science and Industrial Parks in Taiwan

DOWNLOAD THE ZINE

Semiconductor manufacturing is not a linear process. It stretches across time and geographies, entangling people, chemicals, and ecologies.To better represent this, we made a zine that reproduces a portion of this exhibit’s content so it can be read both forward and backward, rightside-up and upside-down. Readers will begin their journeys from either Silicon Valley or Taiwan, and meet each other in the middle, across oceans.